The Great Forgetting: Science Edition

Those who forget their classics soon forget their innovations

My last post, back in early October, made the quixotic case that the Christian church should think about ways to preserve scientific knowledge while we’ve still got the tools for it. The celebrated science fiction novel A Canticle for Leibowitz, by Walter Miller, Jr., offers a fictionalized in extremis version of what this sort of project might look like. In that book, a nuclear holocaust has ruined civilization, but the Catholic church, of all things, has somehow survived. Cloistered monks are slowly recovering knowledge, archiving scientific and humanistic treatises while fending off marauding warlords and mutant outlaws. Eventually, their lovingly preserved libraries become the seedbed for a new scientific golden age.

Miller’s grim and beautiful story hints that preserving knowledge, even scientific knowledge, might not be something we can entrust to scientific institutions themselves. Only a culture of remembering can preserve any kind of knowledge, whether that’s good study design or parsing sentences in Homeric Greek. But in many ways, science itself is oriented toward conquering and supplanting the past. At its origins, trailblazers such as Galileo and Bacon broke with classical and Christian traditions to forge new, skeptical ways of approaching knowledge. The British Royal Society’s motto is Nullius in Verba: “Take no one’s word for it.”

Modern science as we know it, then, is a systematic attempt to figure out what the world is really like underneath all our human biases, traditions, and social constructions. Scientism — what I call Science™ — tries to build a society solely on this mode of knowledge and so is the opposite of a culture of remembering. The more technocratic and scientistic our society gets, the less patience it has for older things, such as the literature and arts that once passed down our common stories and references. Struggling with the Iliad or Goethe’s Faust in the original seems like a boneheaded waste of time if you’re trained to expect immediate input-output relations, or if you see the point of intellectual labor as mastering the physical world as quickly as possible for economic, military, medical, or technological ends. Ultimately, Science™ is a culture of forgetting. But in the long run, this acid ends up eating away the conditions for science itself. This is why we need to preserve its gifts while we still can.

Science as Practice

Because science itself is a cultural practice, dependent on particular skills and bodies of knowledge that have to be carefully learned anew by each generation. Universities, originally founded to pass down the texts of Western culture (essentially, Christendom and its liberal-modern offspring), have increasingly become co-opted for scientific training. Science PhD students learn the skills of their trade — how to use instruments, to run statistics, to think like a scientist — alongside the basic histories of their disciplines and intimate pantheons of revered figures: Darwin, Mayr, and Lorenz, or Heisenberg, Pauling, and Feynman. Science education is entry into a guild, and every guild needs some collective memory to survive.

But we’ve already established that, in a culture governed by Science™, any kind of collective memory is inherently tenuous. I just described the guild training of scientists. The truth is that my description was idealized. In reality, a lot of young scientists don’t really learn the history of their disciplines at all. They start with textbooks and survey classes that present facts and principles as settled but contextless axioms, then they jump to debating papers that were published yesterday and to doing their own original research (or, more likely, their advisor’s original research). Everyone quickly learns that citing too many papers older than, say, five or ten years is suspect. After all, are you a scientist or an historian?

Yet we often need historical context to make sense of the debates and questions that drive current science. Scientists who don’t know the history of their fields can easily risk misinterpreting new findings or reinventing the wheel, muddying things with duplicate terminologies and theorems. This seems to be especially a problem in the human sciences, where every generation invents new terminology for the same phenomena. But it can extend to less mushy sciences, too. A recent article in the journal Automatic Documentation and Mathematical Linguistics found that the field of Bayesian machine learning as a whole had completely forgotten that Bayesian learning is inconsistent when applied to certain kinds of probability models. Professors just stopped teaching this important fact to students, because they no longer knew it themselves. Shockingly — but not surprisingly — the author found that

the reason for the phenomenon of forgetting known scientific facts is a change in the requirements for publications in scientific journals, i.e., references only to modern publications (not older than 5 years).

In other words, professional scientific discourse is so relentlessly focused on the here and now, the cutting edge of research and debate, that facts older than 5 years are simply being lost. Of course, different fields have different standards. In the evolutionary human sciences, where I previously worked, you can usually cite a few sources as old as 20 years. But it looks bad if the median age of your citations is older than, say, 3 or 4 years. Everywhere you look in the sciences, presentism is the only game in town.

Shorten the Time Horizon, Lose the Knowledge

The loss of the past inherently implies the loss of knowledge, because all memories are by definition records of events or experiences in the past. Once the ball gets rolling on the disappearance of scientific history, though, it can be hard to stop, because it feeds on itself. One team of concerned scientists writes that this process accelerates

when professions or scientific disciplines shrink (e.g., if university positions for this discipline are cut) or completely disappear. Although the literature and other information produced by such disciplines still exist, there is (almost) no one left to make this information fully comprehensible and useful. …Consequently, some of the knowledge that had been produced by these dying disciplines and professions is forever lost.

As guild training in the sciences becomes more and more narrowly focused on technical training and dismissive of scientific history, then, the progressive nature of science itself is jeopardized, and institutional memory risks breaking down. If things continue this way, future would-be scientists could find themselves sitting amid a figurative laboratory of instruments they don’t quite understand, theories that are half-comprehended, and books they can’t quite read. They’ll be living out what philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre prophesied in his magnum opus After Virtue, whose first pages conjured a world where

all that [the descendants of scientists] possess are fragments…parts of theories unrelated either to the other bits and pieces of theory which they possess or to experiment; instruments whose use has been forgotten; half-chapters from books, single pages from articles, not always fully legible because torn and charred.…those contexts which would be needed to make sense of what they are doing have been lost, perhaps irretrievably.1

The Great Forgetting

The culture of forgetting in the sciences mirrors the even more dramatic collapse in knowledge of the humanities. In fact, these phenomena are two sides of the same problem. In the journal First Things, R.R. Reno laments that a lot of basic cultural touchstones, from Biblical references to commonplace literary allusions, have rapidly faded from our popular awareness in just a few short decades. He calls it the Great Forgetting. For example (mine, not Reno’s), sixty years ago, any educated person would have been familiar with, say, Ecclesiastes, one of the Bible’s most bracing and literarily fruitful books. Today, it might be fewer than one in four. And we’re talking about educated people, people with fancy degrees. The humanistic core of what was once Western civilization is simply fizzling out.

R.R. Reno is a professional conservative critic, so of course he would think the modern world is going to pot. But in the case of collapsing humanistic knowledge, he’s onto something. There really is a Great Forgetting going on; our educational institutions really have mostly stopped passing down cultural knowledge and references, just as scientific disciplines are forgetting their own histories. Reno observes that

In 1964, Robert F. Kennedy spoke to an audience at Columbia University. He referred to his brother’s favorite quote from Dante’s Divine Comedy, recited lines from Sophocles, and ended with a (modified) quote from Archimedes: “Show me where I can stand, and I can move the world.” By the time Bill Clinton arrived on the national scene in the 1990s, well-placed, ambitious people were adopting a very different manner. They recognized that impressing others now required showing mastery of policy and appealing to economic principles, or some other theory of society. The lens had become scientific and technocratic rather than literary and humanistic.

To compound the problem, as technocratic-scientistic language grew more dominant, universities simultaneously began having a crisis of confidence regarding the Western canon. Students and activists demanded the removal of European classics from courses to make room for more global and marginalized voices. Instead of adding, say, Confucius’ Analects and the Hindu Puranas to diversify the required reading lists, “decolonization” became the hot idea. Yale University, for example, recently canceled a famous art survey source, which had introduced generations of students to the history of Western art from the Renaissance onwards, in order to decolonize — that is, de-Westernify — its curriculum. This came only a few years after Yale had revamped its English major to require fewer classes in the canonical writers — also for the sake of decolonization.

Together, these movements — the rise of instrumental technocracy and the self-critical rejection of the putatively oppressive Western legacy — have had an extraordinary effect on how we regulate our self-image as a society, how we struggle with and perceive collective problems, and how we partake in public discourse. It would indeed be difficult to imagine a national politician reciting Dante and Sophocles today, or even pulling out a quote from Faulkner. Instead of using classic writers as marks of good breeding and education, we’re now much more likely to quote from Malcolm Gladwell, Yuval Harari, or David Brooks — writers who sift through social science to extract pithy insights for quick consumption, often with easy-to-grasp policy implications — or from Ta-Nehisi Coates or Ibrim X. Kendi, who critique “systemic” social problems and offer technocratic solutions such as equity-enforcing constitutional amendments.

In fact, just as scientists avoid citing older papers, it’s kind of gauche among educated secular professionals to reference too many pre–late-20th century writers or artists over a dinner conversation. This reticence comes partly from the fact that (warning: crass generalization ahead) many people in this set believe that all of humanity languished in benighted ignorance from the moment agriculture was invented until about 2012. But it’s probably also because young and middle-aged professionals simply don’t know the older canon anymore. They wouldn’t know who to reference and are embarrassed to try — or it simply doesn’t occur to them to try.

Vanitas Vanitatum, Omnia Vanitas

The loss of memory is like interest: it compounds over time. In Reno’s words, “Baby boomer professors were unwilling to convey the importance of reading Dryden, Pope, and Swift. Today’s rising generation of miseducated professors are unable to do so.” Just as important scientific skills can be lost when we lose interest in scientific history, we can lose the ability to teach our own cultural canon to our children, even if we wanted to. All we have to do is skip teaching it for one generation.

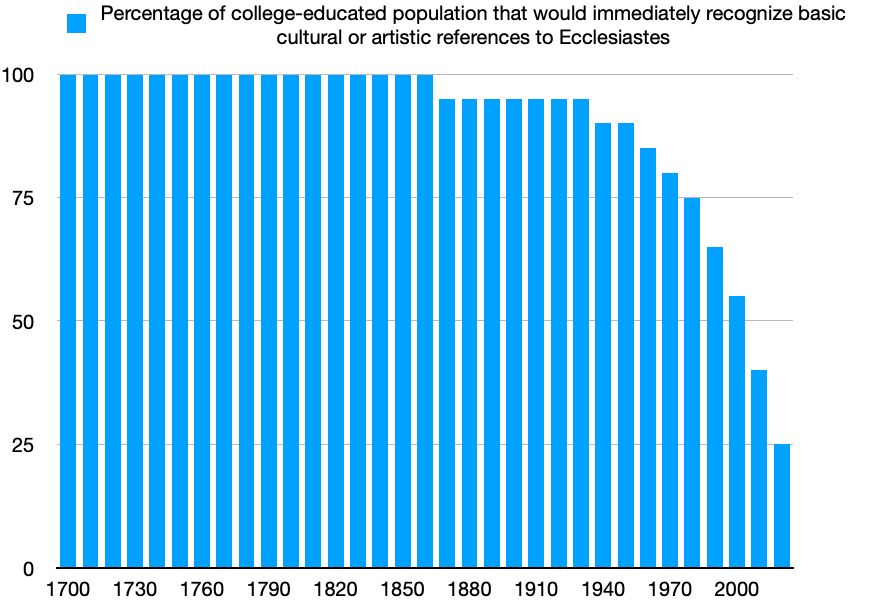

Welp. By this point, we’ve skipped it for at least two generations, maybe three. I like to think about the Great Forgetting in terms of a simple chart. The x-axis is time. The y-axis is the percentage of the educated population that would recognize a basic literary or cultural reference — for example, the Book of Ecclesiastes’ famous observation that “for everything there is a season.” This could be operationalized in terms of knowing the answers to basic questions about the reference and its meaning in context. Who was the traditional writer of Ecclesiastes? (Solomon.) What was his celebrated virtue? (Wisdom.) What pop song from the 1960s referenced Ecclesiastes? (“Turn! Turn! Turn!” by the Byrds.)

You could even simplify the whole thing, making the y-axis the percentage of the educated population who would recognize “Turn! Turn! Turn!” as a riff on Ecclesiastes if they happened to hear it for the first time. The point I’m driving at is that there would be a massive stepwise decline in the past 50 years, after literally centuries or even millennia of extraordinary stability:

I didn’t draw on any particular data for this chart; maybe the proportions would be different year by year. But it isn’t much of an exaggeration to say that literally 100% of educated English-speaking adults in the year 1750 or 1850 (or 1350), regardless of denomination or ethnicity, would recognize a reference to Ecclesiastes. Knowing the Bible and other classical references was what it meant to be educated then. And for all I know, substantially fewer than 25% of college-educated grown-ups in America would be able to tell Ecclesiastes from a backhoe today. People have written entire books about the collapse of religious literacy from a secular perspective. The point is that you could make virtually the same graph for knowledge of Dante, Sophocles, and Shakespeare. Every single touchstone that once served as an anchor for our intellectual culture is fading like the grass of the field.

Lose the Humanities, Lose the Skills for Science

A techno-optimist might ask, what’s the problem? Just because people don’t recognize references to archaic Judean religious texts doesn’t mean our culture has somehow gone down the tubes. We’ve replaced knowledge of the Bible and other “Western” canonical sources with more practical and useful knowledge instead. Maybe educated pre-revolutionary Americans could all quote Ecclesiastes, but today every educated person knows about the genome. We don’t know Dante anymore, but we sure as heck all know Darwin. And every educated adult now can tell you that, um…

[PLEASE STAND BY: TECHNICAL DIFFICULTIES]

Who am I kidding? The truth is that there is no common core of knowledge that all educated people share now. The average business school graduate couldn’t articulate the basic principles of Mendelian genetics if held at gunpoint by a gang of excitable nerds. Almost no one really understands the neo-Darwinian modern synthesis in evolutionary theory, even if they claim to “believe” in it.2 We have scientific-ish ideas that we’re all supposed to assent to as educated people, but few of us actually comprehend them.

Increasingly, we’re all just technicians — narrowly trained to accomplish some particular task, to administer a type of organization, or to program machines to perform tasks that future Trump voters currently do for a living. Yuval Harari and the New Yorker serve as cultural Schelling points for a certain brand of educated person, but they’re not substitutes for the classics. Reading them makes you feel smart the way that mojitos and low lighting make you feel good-looking. As Nassim Taleb has quipped, the opposite of reading isn’t not reading. It’s reading the New Yorker.3

But as our required reading becomes more and more contemporary, as fewer students are forced to struggle through Latin tenses or German noun declensions, the very habits of mind that once made the Scientific Revolution possible are fading out. I know I just savagely roasted the New Yorker, but hypocrisy is the tribute vice pays to virtue, and a bracing recent article in that magazine that covers the crisis of the humanities is worth reading. It quotes one Amanda Claybaugh, a dean of undergraduate education and an English professor at Harvard, on the collapse of basic literacy in young university students:

The last time I taught ‘The Scarlet Letter,’ I discovered that my students were really struggling to understand the sentences as sentences—like, having trouble identifying the subject and the verb…Their capacities are different, and the nineteenth century is a long time ago.

This isn’t a remedial high-school class. This is at Harvard, the supposed jewel in the crown of American higher education and the world’s most prestigious university. In the early 20th century, Harvard students showed up already fluent in Latin and able to conjugate Greek. They had command of mathematics that you or I would shrink from tackling with a high-powered calculator. Today they’re quasi-incapable of reading a novel in modern English that was habitually assigned to high school freshman only a few decades ago.

Now consider that Darwin’s The Origin of Species was published in 1859, only a few short years after the 1850 publication of the Scarlet Letter. If Harvard students are now having trouble parsing Hawthorne, how likely is it that they’re going to comprehend Darwin? How will young scientists and budding technocrats understand the foundations of the life sciences’ unifying theory? Will our future economists be able to read Keynes or Mises?

Conclusion

As the humanities go, so goes science. As counterintuitive as it sounds, we can’t have a culture of forgetting for Dante and Ecclesiastes but a culture of remembering for behavioral biology and machine learning. Either we know how to remember things, or we don’t. And increasingly, we don’t. The institutional and intellectual habits that once enabled us to transmit cultural legacies down to new generations are simply no match for the sandblasting power of institutionalized scientism, with its love of “disruption” and reflexive aversion to anything older than a few years.

I fervently hope the Canticle for Leibowitz scenario doesn’t come to pass, but the idea that the Church may become the fallback for preserving important knowledge isn’t far-fetched. A millennium and a half ago, Christian monasteries at the very edges of the known world preserved classical learning after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Even as literacy died off and knowledge was forgotten throughout the Mediterranean and European Dark Ages, the monks archived and copied writings ranging from Greek and Roman philosophy to the early Church Fathers, building a bridge of continuity between the classical and medieval worlds — and, subsequently, from those worlds to our own.

Today, R.R. Reno observes that it’s almost entirely the Christian counterculture that’s working to preserve older works of philosophy and literature by teaching them to young people. And it’s not just Christian material they’re interested in. If you meet someone who can read, say, Spinoza — one of the progenitors of modern liberal atheism — in the original Latin, there’s a strong chance that he or she was educated in a Christian setting, simply because custodianship of the cultural past (not to mention learning old languages) is increasingly becoming a Christian counterculture thing. My point is that the same may soon be true for the modern sciences, especially their foundations. After a century and a half of evolution-vs.-Christianity polemics, Darwin may soon be kept and studied with loving care only in out-of-the-way Christian libraries, while evolutionary biology PhDs find themselves stumped by his syntax. The Great Remembering will happen where Science™ least expects it.

Thanks to reader KAM for reminding me, after last month’s essay, that I really should be citing MacIntyre for these essays.

The neo-Darwinian synthesis is increasingly seen as outdated, anyway, in part because things like horizontal gene transfer raise questions about the core Darwinian assumption of neatly separable species, especially for prokaryotes (single-celled organisms without cellular nuclei or mitochondria).

Thanks to Rob Henderson’s always-fresh Substack for spotlighting this quote.

Reminded me of Adler's Syntopicon project from around 1950. 35 readers, 5 years, 400,000 man-hours of reading, 434 Works, 73 Authors from Homer to 20th century

https://classicalchristian.org/what-are-great-ideas/

This confirms for me yet again our need for alternative/underground forms of education, and community, and work.

Philosopher-plumbers. Coffee-shop schools. Workshops of community-building.

Back to basics: 1 book, 1 tutor, 1+ students.