Roots and Prestige in Christian Culture

Why integralism will fail, but the church will become the anchor of a new civilization anyway

To be a postliberal is inevitably to get mixed up in questions of what should succeed liberalism and, by extension, modernity itself. As I wrote in my introductory post, I don’t know what’s actually going to succeed liberal modernity, and neither does nobody else. (The most likely candidate in the short term seems to me to be some kind of imperial techno-feudalism of the kind that Joel Kotkin fears, but that’s just a guess.) But in circles where the future of ideology and political organization are seriously debated, some quite radical propositions have turned up. The most controversial and, to liberal-modern sensibilities, shocking, is integralism: the dream of subsuming secular government under the aegis and authority of, yes, Catholic Christianity. This post is brief look at why I think the church needs to take another tack as modernity slips away.

Let me tackle this first at the level of popular discourse. The Catholic journalist Sohrab Ahmari, a popularizer of integralism, sent shockwaves through the educated Christian world in 2019 by writing that Christians should “fight the culture war with the aim of defeating the enemy,” in order to re-order society “to the common good and ultimately the Highest Good.” In other words, he wants Christians to actively acquire social and political power, with the hope of muscularly wrangling society into a shape that conforms to Christian (Catholic) values and priorities.

Ahmari’s ideological foil, the evangelical writer and anti-Trump conservative David French, is horrified by this concept. Instead of angling for coercive power, French believes that Christians should be vigorous participants in the liberal public square under the protection of the Constitution, equally alongside all other creeds. French believes in liberalism, insisting that Christians should take part in public life under the terms set by the liberal system. Ahmari does not believe in liberalism, and he isn’t humble.

To avoid burying the lede, I think that integralism is both undesirable and a pipe dream in America, even though, like Ahmari, I’m no longer a believer in liberalism. In fact, in an ideal world I’d even like to see the church have a hand in ordering society, as flawed as it is. I am a Christian, after all. Either you think your faith has a comprehensive life to offer that is better than other options, or you don’t. If you don’t, then why are you practicing it? If you do, how can you honestly say you don’t wish for a world where your faith claims the lion’s share of loyalties? Let’s not kid ourselves.

But the integralist vision of transforming America back into a Christian nation through top-down, coercive government action isn’t just off-putting, it’s absurd. Even if it were possible (it isn’t), it would be exactly the wrong way to go about re-establishing legitimate Christian authority in a rapidly secularizing society. Instead, the church must lead by serving, which is how real leadership works anyway.

Don’t misread me. I’m not a quietist. My personality is probably more Ahmari than French, for better and for worse. But both the social sciences and common experience highlight that the leader in any group isn’t actually the one who bosses others around. It’s the one who takes care of the others and for the group as a whole, the one who looks out for its agenda: the team captain who makes sure that the field is booked, who schedules and leads practices, who remembers to make reservations for the postgame dinner, who teaches newbies the ropes so they can someday become team captains themselves. These sacrifices often go unrecognized and unthanked (especially by those callow youngsters who have never yet been in charge of anything themselves) but they’re what leadership is made of.

A deep understanding of the nature of leadership at both the personal and the social level is embedded at the narrative core of Christianity, which centers on a vision of God as the self-sacrificial servant leader in the form of a human being. Hoping to assuage liberal sensibilities, I might be tempted to rhetorically over-emphasize the sacrificial part of this formula while deemphasizing the leadership part. I might shy away from creating the impression that the church could be dangerous or martial.

But the church is martial. And leadership isn’t all sacrifice. It’s also leading. And the opportunity for servant-leadership is ripe. There are a lot of gaping holes in the human experience in America right now, a lot of needs that our anomic, atomized society not only can’t meet, but refuses to even acknowledge as legitimate. The need for guidance for youth, for spiritual challenge, for belonging, for identity and meaning, and for continuity — for stability — are only a few examples. A living and courageous Christianity can meet these needs for those who let it whether or not it enjoys any political power. Sacrifice is the path to real leadership.

Dominance vs. Prestige

Psychological and anthropological studies of leadership suggest that there are two basic avenues to high status or leadership in human societies: dominance and prestige. Dominance is the basic animal pecking order. This guy can intimidate or beat up that guy, so he gets to be in charge. Dominance ranking is dyadic, competitive, and zero-sum. It doesn’t concern itself especially with coordinating or directing the group as a whole. The hierarchy in a chimpanzee band is entirely based on dominance. The alpha male is the one who can intimidate every other male in the band, period.

Prestige, by contrast, has more to do with skills, knowledge, reputation, and leadership. One of the core differences between prestige and dominance might be termed magnanimity: generosity in looking out and providing for others. Prestigious people are usually magnanimous, while dominant people need not be. Of course, prestige ranking is still suffused with competition; not everyone can be equally prestigious. But you win the prestige competition by being a resource — of knowledge, experience, goods, guidance, or social connections — not by intimidating everyone else.

Dominance and prestige aren’t necessarily opposites. Many roles in human societies blend both. The Roman paterfamilias was the respected family patriarch who owned the estate and looked out for its affairs. The paterfamilias would lead by coordinating the activities of the household’s members, seeing to the education of the children, planning for its future, performing its necessary sacrificial rites. But he could also dominate by punishing slaves, children, and even his wife, by treating the other members of the family as possessions, and by using his legal standing and his physical strength to get his way.

For much of the medieval and even modern era, the Catholic church was something like a paterfamilias for the Western world. It was able to punish and intimidate, but it was also able to lead, instruct, and cultivate. It was, so to speak, simultaneously high in prestige and high in dominance.

Integralism is essentially the hope that the church will return to its paterfamilias role. As comprehensive individualist liberalism leaves a growing trail of anomie and social wreckage behind it, it’s not just firebrand journalists who are flirting with integralism. Serious and respected thinkers, such as the law professor Adrian Vermeule of Harvard University, are non-ironically advocating for a return to this way of doing things, angling to get the Catholic church back into its role of paterfamilias for society.

Integralism? In a Protestant Country?

You might be forgiven for laughing. We Americans live in the most historically Protestant of Protestant nations, a country that practically was until recently for world Protestantism what Rome once was for Christendom itself: a metropole that anchors the faith politically and spiritually across time and space. Accordingly, Americans who would like the country to be Christian in its orientation (those we now call Christian nationalists) tend to be evangelicals, not Catholics. Ethics aside, who could realistically think that Catholicism would ever have a shot at becoming the dominant faith here, much less acquiring suzerainty over the state? On the surface, it seems laughable.

But as the erstwhile paterfamilias of the West, Catholicism has a long history of deep enmeshment with secular affairs. It’s not just that the pope was the feudal ruler of much of central Italy until nearly the time of skyscrapers. Catholic theologians have long thought and written much more thoroughly and extensively about what Christian society and Christian culture practically entail than their Protestant counterparts (the Niebuhr brothers notwithstanding). Because medieval Catholic leaders were so often involved in actually running states and institutions, from the sprawling abbeys that anchored entire swathes of the countryside to the earliest universities to principalities and empires, they had no choice but to think seriously about these questions. What crimes should be punishable by secular rulers, and which by the Church? How should economies be organized? What values should states try to realize?

This tradition is carried down today through Catholic teaching and cultural infrastructure. Many conservative and/or quietist Protestant churches tend (this is a sweeping generalization) to assume that the culture will go its wayward way, and the church’s job is to save souls by converting people out of it. By contrast, the so-called Catholic traditions (and here I also include Eastern Orthodoxy and, to a certain extent, Anglicanism) see their job as suffusing the cultural order with Christianity.

I’m not even close to an expert in Christian political theology, so I’m not going to embarrass myself any further by trying to tease out the implications and exceptions to this claim. I just mean that some Christians see the church as a holy alternative to secular culture (and, by extension, extrinsic and even oppositional to secular government), whereas others see the proper place of the church as guiding or leading the culture through formal engagement with social institutions. In America, many quite low-church Protestants may lean toward the latter end of the pole, and, again, we use terms like Christian nationalist to describe them.

But only Catholics, and here I specifically mean Roman Catholics, have a comprehensively worked-out, non-utopian vision of the integrated Christian society from top to bottom. I say “non-utopian” because the Catholic vision, whether integralist or otherwise, always assumes the reality of a world where many people are not good Christians, where conflicts will still arise, where you’ll need things like law courts and contract enforcement and even militaries. How will all that secular infrastructure mesh with the supernatural mission of the church?

In other words, because Catholicism has been in charge in the past, it retains a tradition of thinking seriously about what it takes to run a society. You might disagree with the conclusions its thinkers come to, but Catholic political theology is at least not a frivolous pastime. And there is some wisdom that inevitably results from experience in leadership, most importantly the realization that running things is hard. I think it was Orwell who once admitted that Rudyard Kipling, despite being a bigot and a jingo, at least knew the burdens of governing. By serving as administrator in outposts of the British Empire, Kipling had been forced to learn that everything works in tradeoffs, that domineering rarely works, that things often don’t go as planned and you have to work with people to find solutions. So when Kipling wrote about what it took to run an empire, he wasn’t talking out of ignorance or idealism.

Liberal Self-Sabotage

For a similar reason, Catholics often have a leg up on Protestants when it comes to identifying the thorny contradictions within liberalism, the dominant ideology in our era. Put simply, the Catholic tradition encourages thinking practically about power. Vermeule, for example, warns that today’s comprehensive liberal doctrines are undermining the conditions for their own continued political success. He clinically observes that liberal regimes

are compelled…to violate a central precept of the natural art of politics. This is the precept to not unnecessarily disrupt the traditions, the mores and life-ways, of the broad mass of the population, or, where those traditions must be disrupted in substance, at least to preserve the outward forms of tradition.

Vermeule is saying that no regime, no matter how apparently powerful, can survive indefinitely if it denies the basic human craving for cultural continuity and meaning, any more that it could survive if it denied its subjects food. Starving people will eventually revolt. You have to at least not actively thwart the most basic needs of the people you’re trying to govern if you want to retain your political capital and stay in power.

This is practical politics.

But liberalism isn’t in a practical phase. It’s in thrall to idealism and utopianism, which do not care about people’s need for meaning or continuity. Vermeule continues:

Liberalism is incapable of respecting this constraint [i.e., the need to avoid unnecessarily disrupting the traditions and cultures of subject populations] because to do so would betray its inner nature, which is to publicly and conspicuously celebrate its great liturgy, the Festival of Reason, the dynamic overcoming of the darkness, superstition, and slavish authoritarianism of the irrational past.

Here, Vermeule is speaking from knowledge derived both from Catholic political thought and experience with Christian liturgical life. Catholics tend to understand the essentially liturgical character of society better than Protestants — its origin and anchoring in ritual. So, for critics such as Vermeule, it’s more obvious that the rituals of liberalism are rituals than this might be to others. And he’s not wrong: liberalism is more and more revealing itself to be something religious, a non-neutral, comprehensive worldview centered around a liturgy of repudiating and overcoming our past, over and over and over again.

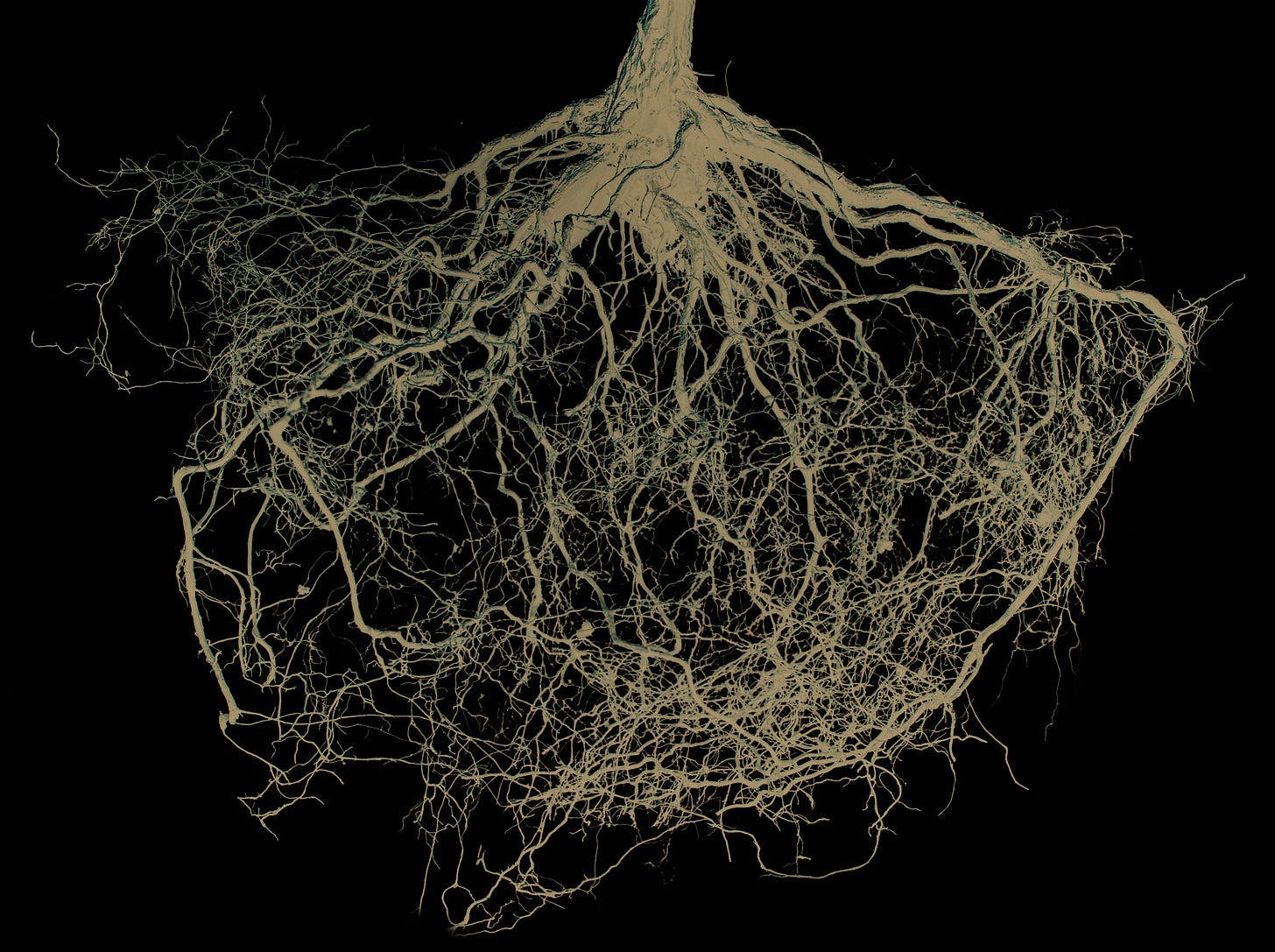

In our milieu defined by this liberal liturgy, people will inevitably have a hard time meeting the basic human psychological needs for moral community, meaning, continuity, and companionship, because the wider social order actively opposes those needs. You could sum them collectively as “the need for roots,” as Simone Weil put it. We are having a terribly hard time, in fact, meeting this need already. Vermeule and other postliberal critics, including integralists, are onto something when they criticize and warn about the disaster.

But the church — Catholic or otherwise — can’t, and won’t, respond effectively to it by pretending to be the paterfamilias again. The dominance side of leadership just isn’t available to it now. Instead, the church must acquire prestige. This will be most easily accomplished in the way that prestige is always acquired: by providing and looking out for the whole. By being magnanimous as the grownup in the room. The church, in other words, should be doing all it can to provide roots, which is exactly what the secular order is incapable of providing and even officially hostile to. It’s the time for magnanimity, not coercion.

The Church as Uncle

So the church can’t be the paterfamilias — the respected family patriarch, setting down rules and guiding affairs — anytime soon. The family, America, is far too dysfunctional for anyone to govern effectively at a spiritual level, much less an organized religion that’s collapsing demographically and institutionally. A major meteorite strike directly on the Apple headquarters at the instant you read this would be more likely than a return to a formally Christian nation.

But this doesn’t mean the church should turn away from society or head for the hills to lick its wounds, as some people think the Orthodox journalist Rod Dreher is arguing for in his Benedict Option. I think that todays’s integralists, such as Vermeule and Ahmari, are doing us a favor by thinking seriously about how a Christian culture would counteract many of the problems of liberal modernity, particularly rampant anomie and rootlessness. I see integralism as actually compatible with social-scientific insights into the nature of human culture and cognition: namely, that culture is always built on rituals and unfalsifiable beliefs and tends therefore to become sacralized.

In other words, there’s always going to be a tendency toward some form of “integralism” in every society, at every point in history. Prior to the 20th century, the vast majority of nations and empires were officially religious. That’s not coincidence, and in a way it’s true today, too. The unfalsifiable, ritualized worldview that’s entwined with our American empire today just happens to be utopian liberal secularism, but, despite its name, this worldview turns out to be surprisingly religion-like. Again, liberalism is not neutral.

The ascendancy of utopian secularism means that we really do live in a post-Christian society. Serious Christians are a minority in the West, one with decreasing influence. But we still possess the living cultural memory of Christendom, of which America was very much a part. To many Christians, then, it still seems reasonable to hope that we could get back there somehow, by electing the right officials or making the right laws or making the right appeals to the public. Integralists like Vermeule would like to accomplish this return of Christendom in the United States by using the architecture and coercive power of the state to enforce Christian values on an ambivalent populace.

But look at the way the overturning of Roe v. Wade galvanized left- and center-leaning voters in the recent midterm elections. Americans in the 21st century are not going to accept Christian values by legal fiat or government coercion. And they’re not showing much interest in returning to the faith voluntarily en masse.

So the church is not going to be the paterfamilias. It’s not going to govern the family. The family doesn’t even live at home anymore.

Instead, to continue with the family metaphor, the institutional church needs to become something like the stable uncle in a wider family otherwise ravaged by delinquency and bad decisions. An uncle who has, against the odds, kept his life together, who maybe went to college, who keeps a good if rambling house with a wild and fertile garden out front. He and his wife have a good marriage, a striking contrast to the serial failed relationships of their various nieces and nephews.

As the stable one — the grownup in the family — this metaphorical uncle isn’t beset by constant emergencies and crises. He’s able to think about the future, about the greater good. So he checks in on the nieces and nephews and their travails, their fissile relationships, their constant troubles. He persistently, patiently invites the wider family, year after year, to Christmas dinners, to Easter dinners, even though they largely ignore his invitations. Some of them even despise and resent him, insulting him behind his back. Who does he think he is, with that big house and his preening kids?

Crucially, this uncle and aunt are the only ones in the wider family who keep the family treasures: the family records, the invaluable old correspondence, the old china and jewels, the carefully preserved books of genealogy. One bookshelf is dedicated to the novels that one world-traveling great aunt wrote. The patents for inventions by the great-grandfather are framed in the hallway. The centuries’ worth of awards, the beautiful wood furniture, the drawings and paintings: it’s all still there, all still gleaming. But the hallways are lived in. The furniture is broken in. The house is no museum.

Most of all, this uncle and aunt (the church) preserve the habits and outlooks that once made the family (Christendom) great: the shared dinners rather than solitary meals in front of screens; the morning prayers that still and concentrate the mind and invite divinity into the day; the insistence on reading literature, on education in music; the active remembrance of the past.

The scattered nieces and nephews don’t understand that the uncle collects and preserves the family treasures in preparation for the day when the family will be interested in them again, not as objects of brute exchange, but as pieces of a story. Let’s be honest: grandma’s diamond engagement ring is better off with the uncle than with the cousin who’ll pawn it off to buy another xBox. The uncle knows the story of how it came to her, and he’ll preserve both the ring and the story for future generations.

The last remaining grownup in a once-great family doesn’t turn his back on the tribe. He doesn’t sell the rambling old family seat and withdraw to the hills in bitterness. He persists. He offers love, leadership, and stability, even when they’re rejected and ignored. But he doesn’t try to reestablish the old family authority, either, telling the nieces and nephews what to do, ordering them here and there. Nobody would obey.

The trick is this: over time, the uncle’s household will grow again in influence, in prestige, because stable people and stable houses always become anchors. Here and there, a battered niece or nephew may show up on the stoop, maybe weary of the constant chaos at home, maybe curious to see one of the old paintings or books. They’ll notice the feeling of peace inside this rambling, great, dark and delightful house. They’ll realize with surprise that the treasures there are worth looking at, getting to know.

And slowly, the uncle’s household, his circle of confidants and mentees, will become the home base, the seat, for a new reconstruction of the family. People will start coming to his Christmas dinners again, not from coercion, but because the warm glow through the glass and the sound of piano in the dark winter night are so lovely. They’ll come because it will sound and look so much like a home they never knew, but somehow remembered.

Culture will always be inherently religious. Christians aren’t wrong to want a Christian culture. But they — we — won’t get there by forcing it through the institutions that already exist. We’ll get there by building a net that can catch people — a home that people can return to when the weight of homelessness becomes too great to bear. And we’ll keep looking out for the good of the entire family in the meanwhile, keeping up the invitations, preserving the family gifts, setting up secret trusts. That’s leadership. To return to a metaphor inspired by Weil, this will mean cultivating and offering roots in an era of total, enforced rootlessness. It will require hard work in the dirt. But no one else is offering roots. Everyone else is cutting them. He who plants the roots harvests the garden.

This essay is a beautiful example of why stories are so much more powerful than ideologies.

Thank you for writing this! It has provided me a better understanding of my own naive/nascent thoughts on this subject. I am very much in line with your thinking on this but hadn't realized how deep and complex this subject is.